On Sowing Seeds and the Wonder of Germination

An interview with Fritz Haeg, the artist and founder of Salmon Creek Farm, on behalf of our recent seed mix collaboration

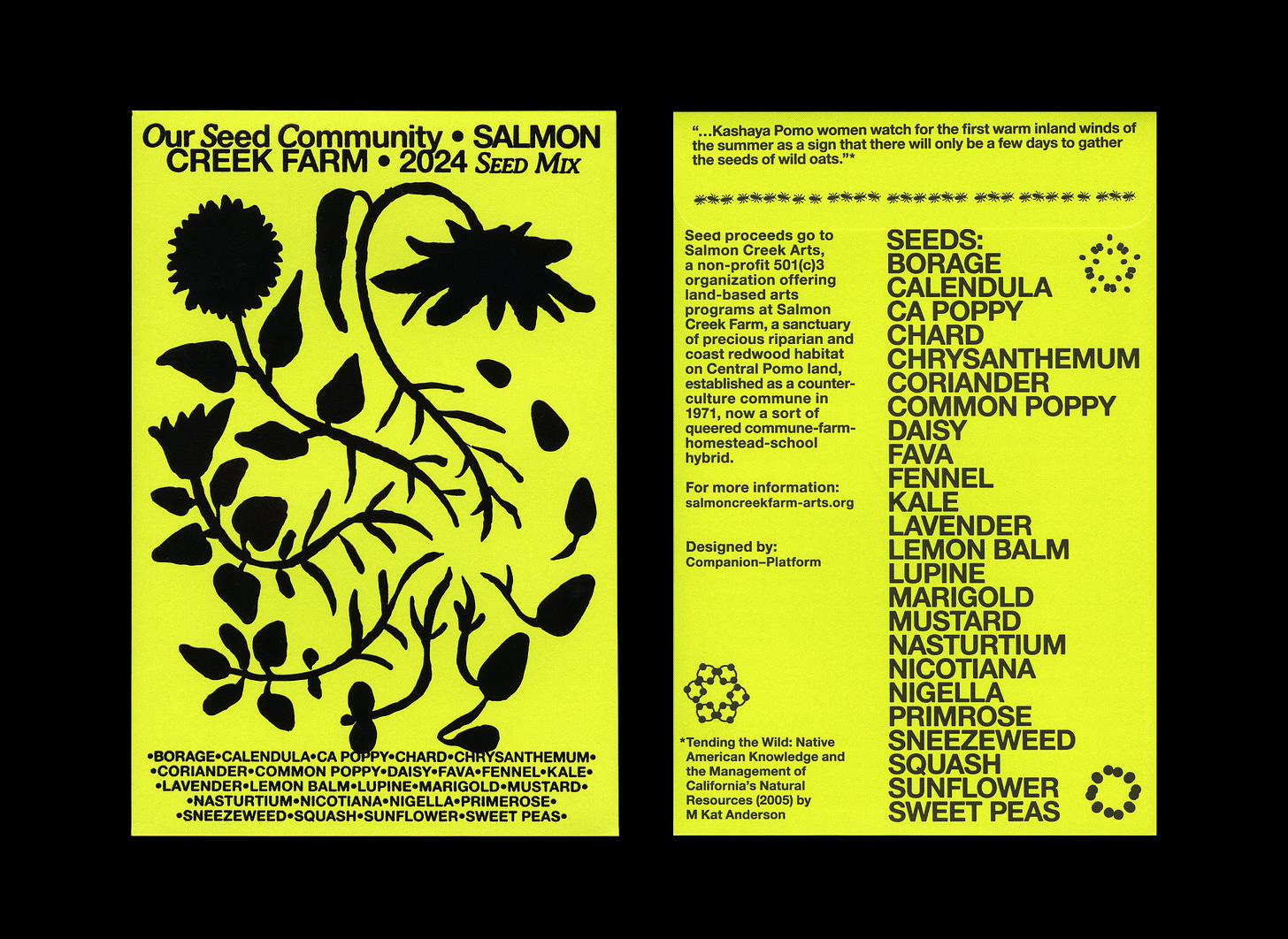

We are very grateful to have had the opportunity to speak with Fritz Haeg of Salmon Creek Farm, on behalf of co-launching their 2024 seed mix, Our Seed Community. Salmon Creek Farm is a sanctuary of precious riparian and coastal redwood forest habitat, on Central Pomo land, established as a counterculture commune in 1971, now a long-term living art project shaped by many hands, a sort of queered commune-farm-homestead. They recently initiated Salmon Creek Arts, a non-profit 501(c)3 organization offering land-based arts programming. All proceeds of the Seed Mix go towards this coming years programming on the land.

You can purchase the mix here, which includes 24 varieties of greens, grains, flowers, edible cultivars, and native wildflowers collected by hand at SCF, an editioned seed packet, and a special bandana that illustrates the score for sowing.

We were excited to speak with Fritz more in depth about the practice of seed collecting, scores and cycles on the land, and the childlike wonder of germination that feels more urgent now than ever.

❧ Companion–Platform: Can you describe the garden at Salmon Creek Farm and the environment from which the 2024 Seed Mix was gathered?

Fritz Haeg: There weren't really any gardens when I got here, maybe around 25 fruit trees planted in the 70s. I bought the place 10 years ago, and have been gradually cultivating the land more and more along with whoever's around at the moment. The garden is a huge part of my life and the thing I'm most passionate about on the land. It is allowed to grow increasingly chaotic through the season. In the spring you'll see a structure of paths and beds, and by this time of year (early December), it's a chaotic mess with volunteers growing in the middle of the paths that are allowed to be there, and things getting pretty rangy and out of control in a way that I love. I like a garden where things aren’t in rows, there's kind of a freedom about where things are planted. There are “neighborhoods” of certain things like perennial herbs, annual vegetables, and flowers. And there is a strong structure of the fruit trees, which anchor circular terraces of little permaculture companion gardens containing things like lemon balm, sage, ground cherries, chard, kale, and primrose and others that have naturalized — coming and going, needing almost no water through the summer. The more highly cultivated and tended vegetable garden beds that need more attention are closer to my cabin.

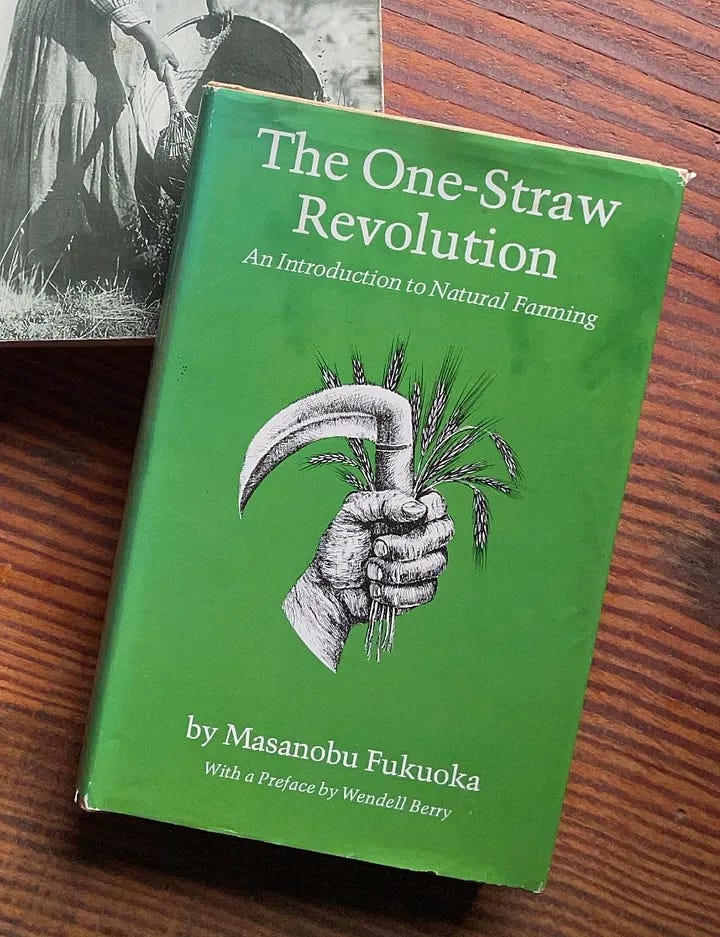

We have a border of perennial low water native plants that were just planted in the spring. But the garden is a balance between anchors of perennials and trees that we design around, and then a culture of annuals that are allowed to naturalize — the kales and chards and leafy greens and flowers that are allowed to bolt and set seed and dry up and return the following season. You can go through the list of the seed mix this year and you'll see a lot of these plants. A big part of the garden is letting things naturalize. One touchstone for me is One Straw Revolution, the 1975 book that promotes a kind of wild landscape that leaves plants for their full life cycle, which includes drying up and dying in place, which is a huge part of it.

❧ Can you speak to how you think about the garden at Salmon Creek Farm as a kind of mother garden, and its relationship to the spaces in which people will be sowing these seeds? We know that was a big part of your work early on, and continues to be through this seed mix project.

That's an interesting point. I spent 10 years doing a series of Edible Estate gardens around the world, working with families to publicly grow food in front of their houses. And then the Wildflowering LA project that was 50 sites around LA County. Those projects promoted an attitude towards design, art, and landscape that was trying to short-circuit the top-down, dictatorial, singular masterpiece model that we have in our culture, that says, “I'm doing something that nobody else can do, and I'm going to protect it.” I'm actually doing something that anyone and everyone can do. And everyone who wants to is invited to do so. And it undoes this idea of authorship, control and the notion of the solitary genius. It’s a way of catalyzing things that are bigger than yourself that is really important to me. And the seed mix is made in a similar spirit — gathering these seeds and sharing them as a way of taking what we're doing at SCF, and inspiring others to do something similar.

❧ It truly feels like the invitation of the seed packet. The seeds come from a place that is geographically rooted and not everyone has access to or can physically visit, but contained in the seed mix is the possibility of recreating the spirit and ethos of Salmon Creek Farm.

This idea of insemination, stemming from seminary, is something I’ve played with before. My previous home, a geodesic dome in Los Angeles, was a center for gatherings and salons in my own garden. The last program we did there was called a seminary, and it lasted for three months. If you look at the root of the word seminary, it comes from this idea of having an incubator, a place where you're starting seeds, or gathering seeds and spreading them — sharing and using your home, or in this case the commune, as a place to generate a kind of wealth that goes out into the world in some way.

❧ Part of the language we've utilized in association to the seed packets is this idea of it being a “score.” How do you imagine sowing these seeds as a score?

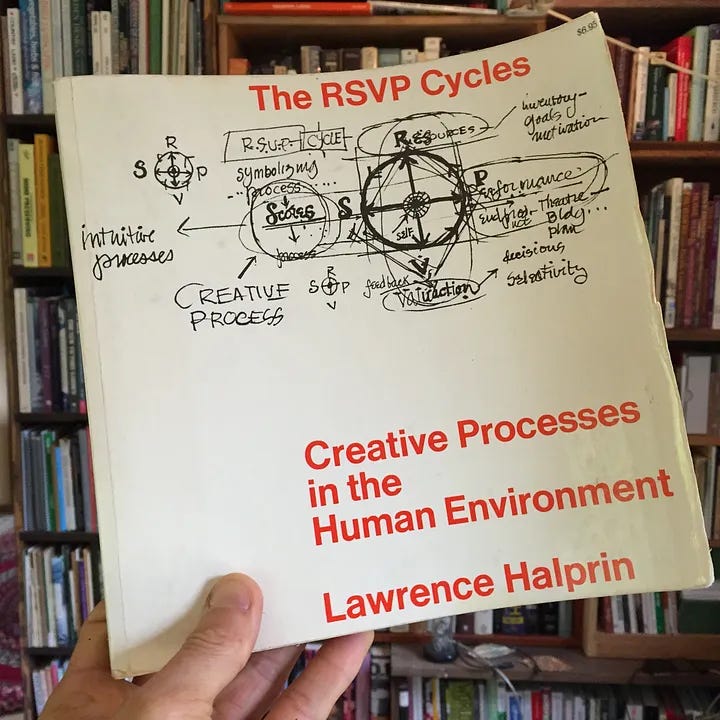

Well, of course, we share a common interest in Anna and Larry Halprin. And the Halprins worked a lot with scores, and used the strategy of a score outside of how it's conventionally used in music or even dance, and looked at scores in terms of activating public space. People who receive these seeds may not know exactly what to do with them or how to sow them because it's an unusual seed mix. It actually makes no real sense commercially, but it makes complete sense “naturally,” because that's how nature operates. “Nature,” has this great abundance of seeds that are pouring out constantly in chaotic ways, and are deposited into the landscape into a seed bank, and they're activated at certain times of the year depending on moisture, temperature, and sun exposure. We're putting this mix of 30 seeds out into the world, and into very different climates. People are going to be sowing them at different times under different circumstances. And a score is important because it offers people a prompt to perform to make the most of these seeds on their particular piece of land, at whatever time they are sowing them. And the score in this case involves simple measurable things that the Halprins would have been interested in too, like the resources required — the size of the land, water available, time, etc. It's like Anna would say, “we're telling you what to do but not how to do it.”

❧ The prompt of a score is very exciting to us, as it inherently contains direction for movement, but it's open to interpretation. And thinking about a garden in movement or how things are naturalizing, volunteers are moving into the pathways, etc. With this openness of interpretation to a score it also leaves room for other species that are distributing seeds and moving seeds around. And something we felt really excited about is the notion of a score being open to interpretation to other species alongside the people that are sowing the seeds.

It also primes whoever stewards the seed packet to be thinking on different time scales. I think oftentimes the visual language of seed packets is very much like “you are putting this in the ground and waiting for it to bloom.” And the SCF seed packet as a score, and also as a set of cycles, means you're moving through it with us. This establishes a relationship with both Salmon Creek Farm, but then also the seeds that you're caring for at every stage of their life cycle, especially with emphasis on letting them go to seed.

It also pushes against this new world of attitudes you can see in our culture today around optimizing wellness or maximizing efficiency. This is a very inefficient program of sowing seeds. It operates the way these plants tend to operate in the world, which is sowing way more seeds than they need to because it's a very inefficient model of distribution, usually, where most seeds never germinate or produce at all. And I think the attitude of sowing and nurturing these seeds is very different from sowing them in a perfect row and watching each one of them germinate and produce for you. They're not all going to do that here. It's much more wild and chaotic.

As someone who's been gardening for over 35 years, to this day I feel like planting a seed is crazy and makes no sense at all. In the back of my mind, there's always this feeling of surely this can't be right. It still seems like a miracle that it happens at all. And every time there's any germination, it truly feels miraculous. I still can't get over it. There's a reason why children plant seeds in milk cartons on day one of school. It's fundamental. And it's the wonder of that miracle that I think we need to witness and remind ourselves of, outside of production and maximization and sustenance and whatever. It's that wonder of planting a seed and watching it grow, period, full stop. Like, that's it. That's beautiful.

❧ Can you share an intention for everyone who sows these seeds? In what ways does the act of planting these seeds feel vital?

The very act of sowing a seed and watching it grow is urgent. It's something that I think people who aren't able to have a garden, or live a life in relation to a piece of land where they're growing things, in some small measure can have these seeds as an opportunity. You might receive these seeds as a gift, let's say, and then you look around and you're like, “Oh, where am I going to plant these?” And I kind of love that first act of questioning where to put them. You start opening the door and looking around outside and are like, “Okay, what's worthy of these seeds?”

❧ Amy Franceschini (a mutual artist friend) mentioned to us that she has a special container out on a fire escape that she saves for seeds that were given to her by friends, and whatever they are, she tosses them in there to see what happens, making for a very rambunctious friendship garden. And we thought that was very beautiful.

Can you two talk a little bit about your thoughts about the mix this year and what your intentions were for the design language of the package and the bandana?

❧ A quality we were thinking a lot about in both seed packets [including the one we made together in 2020], is when something is slightly enlarged and bigger in scale than you are accustomed to, it feels like it has this kind of childlike quality to it. We're really fascinated by older designs of children's story books and how the font is slightly larger in scale than you're used to, the scale of insects and plants and things are all kind of enlarged. And that's a variable that we were trying to be thoughtful in playing with — it's like you were saying before Fritz, there is this kind of childlike wonder in watching a seed grow and germinate and no matter how many times you've done it, there is this magical quality to it. And we were really trying to create an experience of the seed packet as an object that felt congruent with that kind of wonder.

Also we placed a great deal of emphasis on cycles. We have worked on designing a few seed packets now, and it's been interesting gifting them to different friends. Something that we're always struck by in people is how quickly they identify themselves as not having a green thumb, and feeling very intimidated about trying to grow something. And something we wanted to build into the design language is an emphasis and celebration of one's relationship within cycles larger than themselves.

Can you talk about the design language of the bandana in that way?

❧ The starting point for us was how to create a circular score, but then also make visible and celebrate the mixture of flowers and plants included. We drew the inflorescences of all the species contained in the mix, and pulled some of the whimsy from our previous seed packet that we created in 2020, infusing the diagrammatic quality of inflorescences with ornamentation and abstraction, gesturing at the movement of seeds and the rambunctiousness of these organisms.

The bandana is very dense with information. The score is 12 points, each one a paragraph, and then diagrams and illustrations. And after it's been used to sow the seeds, you can wear it or put it on your dog. It has this quality that I love that feels akin to Dr. Bronner's, where there is this insane density of information that is the opposite of this branding culture we live in, of the reptilian brain of only communicating what can be understood at a glance. This demands that you really go deep. You could really spend a lot of time with this. And it's beautifully done.

❧ And the cycle of the score continues! The score as it is visualized on the bandana only has a beginning, and no end. The seeds from these plants can be collected, and the gift of germination continues.

That's highlighted at the end of the letter that we've included in the mix. At the end it says, “We hope that you'll collect your seeds and share them in your community.” It truly boggles the mind when you think of the fractal nature of that kind of infinite sharing that could go on…

❧ Embedded in the potential of these seed packets is the promise of care, generosity, cross-pollination, and connection to others, both human and non-human. These feel like ways of being and values that are vital in this moment.

Purchase the SCF 2024 Seed Mix

Love the bandana as a “score”! Very Lawrence Halperin.

So enjoyed this! xx