An Ode to the Observational Platform: A celebration of the places from which the world solicits our attention

An interview with Kevin J. McGowan, Ph.D., of Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s Bird Academy.

We could barely hear the sound of our footsteps on the mulched paths and hovering boardwalks of Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s Sapsucker Woods. Green light trickled down through dense foliage to the pond bottom, where insects dashed between rooted worlds of the forest’s waterbody. It all felt as though it was actively absorbing, absolving and metabolizing distracted minds of visitors, soliciting attention as a ripple out into the worlds of other species.

We were moving slowly when a kind and curious voice, a voice we would soon recognize as familiar, asked what we had seen that day. It was the voice of Kevin J. McGowan, a momentous individual behind Cornell’s Bird Academy, and the instructor of an online course on crows that we had taken several years prior. Kevin was attuned to the forest, and the whole landscape seemed to further come alive as we looked together. Mid sentence, he quietly gestured towards a Pileated woodpecker flying over the pond, and we were not so quietly overwhelmed by the sight. We had been hoping to see North America’s largest woodpecker for as long as we could remember, and of course one emerged while standing there with Kevin, as he just seems like one of those people, where the world becomes that much more animate in their presence, and these kinds of encounters with other species feel all the more special.

❧ Companion–Platform: how would you describe the Wilson Trail that circumnavigates the Sapsucker Woods Pond, and how has this forest evolved as a protected bird sanctuary?

Kevin J. McGowan: well, I'll answer the second part first, which is to say the sanctuary didn’t exist 100 years ago. It was named because it was the only place in the area that the local bird-interested people found Yellow-bellied Sapsuckers nesting. That was a big deal, so that's where the name comes from. In the late 1950s, the sanctuary was donated to Cornell University and a building was built to house the lab of ornithology, which was actually just Arthur Allen, the first professor of ornithology. He taught ornithology at Cornell, got his PhD here working on red-winged blackbirds. He was hired by the entomology department, where they study insects, so everybody was interested in insects except for him. And so he said that he put a sign on his door saying, this is the laboratory of ornithology because we study birds here. There was a wealthy donor who loved what Arthur Allen was doing. He did a lot of public outreach and was a very eloquent guy, wrote a lot of articles in magazines and things like that, and just a really magnetic person who did some really amazing things. And so they built this place — I don't know what it was before they built the sanctuary here, but the main woods itself had been cut once, back in the early 1800s, but it hasn’t been cut since then.

The northern part was basically grass when the observatory was built. Certainly, from that time in the mid-1950s, this was a protected area that was created as a sanctuary for people to enjoy and to look at birds. The Wilson Trail is the trail that circumnavigates the pond, so it's sort of the heart of the sanctuary. And yeah, it's a great place to go and take a walk. And I'm so lucky that I get to do it every day.

❧ Can you describe how your attention shifts when you leave your office and walk out onto the Wilson Trail? How long have you been taking walks and observing birds from the path?

I've been visiting the Wilson Trail since I got to Cornell 35 years ago and would visit the lab. I did not work at the lab at that time, but rather in a related department. And I definitely took walks here. It's a good birding spot during migration, so it is one of the better places in the area to come and try to find migrant warblers and species like that. I've been doing a consistent noon walk with one of my colleagues here for almost 10 years.

I'm always much more likely to go for a walk in the woods than I am downtown or a place like that. I grew up in a small city, I was a city boy. We had a quarter acre lot and sidewalks and all of that stuff. And that was not where I wanted to be. I wanted to be living in the country somewhere. And fortunately, my grandparents had a farm and that's where I got to be in the woods. I was going out and walking around in the fields and the stream that they had there. So for me, walking on the trail here is not just exercise, but it's a green space that I can go look at. And that is really important for me — I need green. And even though a lot of the time it’s not green in Ithaca, when it comes, it comes. And it's just great to be able to stop worrying about whatever I've been worrying about and go out. And I hope to find birds, but I honestly don't need to see birds to make it a successful trip. It's always good. Take a deep breath, let go, and let's go see what has changed or not. I see if I can find a frog or a turtle. Every day is a better day when you see a turtle, right?

We have this spot at the base of the boardwalk that my friend and I were looking. It’s this little area that drains and we kept checking it every day for a period of two years or so. And we experienced so much drama in that one little pool. We took one of our co-workers out and we stopped at this pool and said, “you'd be surprised how much action there is here.” And while we were watching, there was a dragonfly that was coming down and trying to lay eggs in the water. At that moment, it got caught by a predatory backswimmer bug. It grabbed the dragonfly so it couldn't fly away, but it couldn't do anything else with it. And the dragonfly was struggling to fly and was gradually moving both insects to the side of the pool. And then a big green frog tadpole tried to interfere and see what was going on, and finally the dragonfly got the bug over to the shore, and it let go, allowing the dragonfly to fly away. We said “well, we don't normally have that much drama here every day, but you never know when you're looking into these little places.”

There's a whole lot of wonder all over the place.

Yesterday I went out with my colleague (a snail expert) who looks down while I'm looking up, and she was finding all kinds of little creatures. We didn’t make it very far. I had to remind her that we had to be back for a meeting, and would never make it all the way around the pond in time. And it's so much fun. Every day is a new adventure, or hoping for one anyway.

❧ What an incredible thing to have colleagues who also share that deep pleasure of observation…

It's fun because everybody brings different knowledge to the place, and that's what I love. And chances are, the next time you take the walk you've been on dozens of times and you do it with somebody who looks at snails, it's going to be a different walk. And you're going to see a different part of the world. And that's spectacular. That's something I've looked forward to doing basically every day of my life. It's very beautiful.

❧ Pardon us for asking this, but do you find that a snail specialist moves through the world a little bit more slowly than others?

Yeah, a little bit [laughs]. It’s fun because she had a vendetta on spongy moth eggs that used to be called gypsy moths. And last year we had a bad outbreak and every time we would go through the woods she would try to scrape off the ones she saw. And we went the same way maybe ten times and she still kept finding more. And then we went the opposite direction on the path and she was all upset. “Oh my god look at all the other ones we missed!”

❧ What are some of the most memorable experiences you've had observing birds, or other species?

Almost every encounter I've had with a Pileated Woodpecker has been pretty special. I've seen them digging out a nest hole, and there was one that was working on a fallen log right off the boardwalk that allowed me to get really close and that was spectacular to witness these animals take apart a tree.

A number of years ago, there was an American Woodcock that somebody spotted and got everyone’s attention in the building. We all went out and watched and photographed it. They do this bobbing walk, and ostensibly it's to get earthworms to respond by trying to move out of the way and then find them, then they reach down and stick their long bill into the soil and slurp up this earthworm. It's really amazing to watch. Woodcocks are amazing birds. They're a shorebird that lives in the forest. One of the neat things about them is their eyes. All birds' eyes are on the side of their heads. But their eyes are up higher, so they have almost a 360-degree field of view. I think it's 354 degrees or something like that. So, they can be facing directly away from you, and you can still see its eyes. It’s such an experience to sit and look at this thing up so close while they are in a different world. They can open just the tip of their bill, called rhynchokinesis, allowing them to reach down into the soil and grab the earthworm without opening their bill entirely. It's really quite remarkable.

❧ It’s so wonderful that you were able to share that experience with your colleagues.

Yeah, and get to see it foraging too. They have a display where they start making these chirp, chirp, chirp, chirp, chirp, chirp, chirp calls, and then they fly up into a big circle, twittering the entire time. They have special tail feathers that make noise when they spiral down. And the whole time you’re trying to get a look, where is it, where is it, where is it? Bing, it's on the ground. That's the most experience observing them I've had is watching them do their display flights in the evening.

❧ Something that we deeply enjoy about the practice of birding is getting to experience it and share it with others. It's a matter of a slight shift of awareness and sensitivity, and the barrier of access feels very low. And it makes so much sense to then experience and share that shift of observation or noticing with others.

I definitely find it that way. And I find the thing I like about birding is that it's easy enough to get started and to be able to enjoy new things. Anybody can see a sparrow and feel happy. But it's challenging enough that it'll keep you working your entire life to find new things and get better at seeing. It's fun that way. And one of the things that birding has given me is an understanding of how complex the world is. We walk by 99% of it without noticing, and the 1% we do notice, we misinterpret. We can’t see how deep the pool is. That's the thing. You come up to a lake or a pond and you say, how deep is that? You can put your foot in, or you can walk in, and if it gets over your head you have to swim. It could be a thousand feet deep or just 10 feet deep. And for me, birding has allowed me to get some sense of how deep the world is, and that I had no idea that there were so many different species of birds. And to me, that's the way I look at the world, I know how many birds are where. And that's how I understand the depth of the water is through birds. And I know that this is just one tiny, little aspect of it. I had a friend who was an entomologist, and he was useless when you asked him to do something outside, like help move firewood, because he'd always go, “oh, look at that beetle.” Walking from the car to a picnic table, he'd stop to find 10 different things. If you're an entomologist, the world is never-ending, especially if you like beetles, because there's so many of them.

That's why I treasure going out into the woods with people who know something different than I do. Because I know I'm walking by most of life without noticing it.

When we can share our little focuses here and there, it pleases my soul to be able to do that and to be able to have somebody share something with me that I wouldn't have seen otherwise.

❧ It's so beautiful to think that in place of an encyclopedic knowledge, that you can have a social experience and share these acts of noticing with other people who specialize their attention in these different ways — a necessary interdependence of knowing the natural world.

And it can be very social. I'm a fairly observant guy, but I can't see everything, and I love it when somebody shows me something that I missed that I'm interested in.

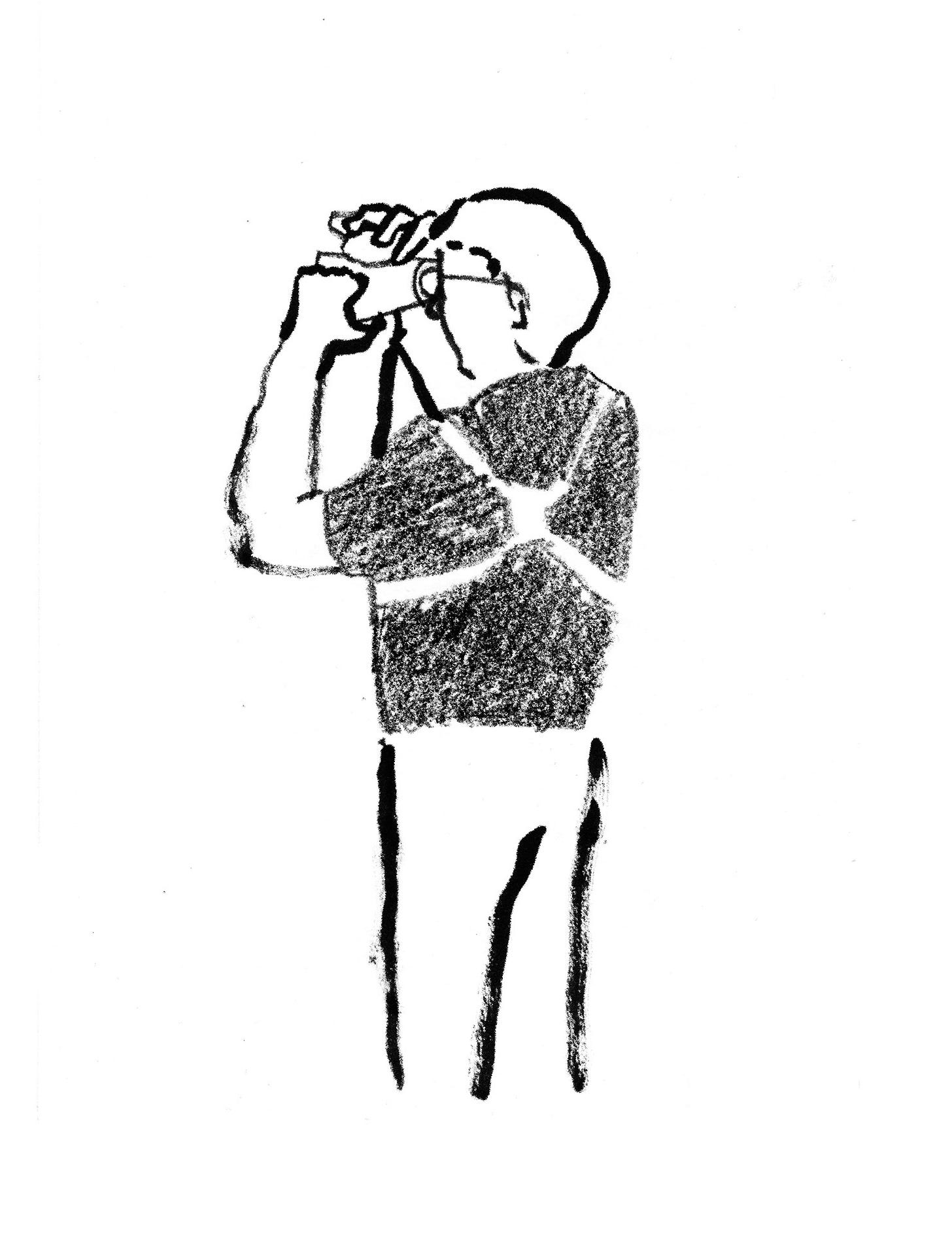

❧ We spend a lot of time on the trails in Berkeley and in Oakland, and something we've been noticing is when you see someone, a stranger, on the side of the trail listening or observing something, or with binoculars, it feels like an invitation to ask them what they're paying attention to. And in contrast, when someone's looking at their phone, it feels like the opposite, that they're not open to an interaction. But we really love how the body language of observing can be a really special invitation to just talk to this person, like the way that you approached us and asked what we had experienced on the trail that day. It's really meaningful to get to share these kinds of experiences with other people and connect.

Yeah, it is. I am an educator, so I've been at this a long time, but for me, when I look around, it's like, who can I tell and share this with? Who can I show this to? And fortunately, most of the people that really get into natural history are really nice people [laughs]. And they really love to share their knowledge or learn from somebody else.

For a lot of people, I think it fulfills this sense of going out and collecting something that I think is very primitive in our makeup. This idea of being able to capture something and bring it back, something that is almost lost these days. It still feels so prevalent in some of these naturalist circles, the act of capturing something and bringing it back as a story or an experience in which you are able to share with others. A lot of it is storytelling. It used to also be food, and now it's more food for thought, but that's still good, right? Going out and being in nature and existing with nature is a very complex issue. And there are so many layers of how you do it, or don't do it, and what you get out of it and what you put into it.

❧ What are some of the signs you've come to observe that signal a shift in seasons in the Sapsucker Woods?

Well, the first thing that comes to mind is there's a swamp red maple on the back side of the pond that is always the first tree in the late summer to begin changing colors. There's that maple changing, so it must be that summer is coming to an end. That’s an obvious one because it's the first tree that changes like that. And it's been like that for 10 years or so, that I've noticed that tree, I watch it to see when things are starting to change. On the flip side, in the winter and early spring, we start to see things like skunk cabbages that produce heat. And if they're covered in snow, they’ll melt it, so there'll be little circles around the skunk cabbage.

❧ Considering observation as a tool for learning, what do you feel the Wilson Trail as a learning environment can teach you, a class, or the institution at large?

The thing about the Wilson Trail is it's easily accessible. It's not handicap accessible yet. And that's something that the lab is working towards. But it is accessible to a lot of people. Even if you only get out to the boardwalk and look from there, it's different. It's not wilderness, but it's a little piece of the world that's green and has creatures living in it that you can find.

There is life and death in the woods. It's not the whole world here, but again, it can be a clear lens through which to peer into the larger natural world.

Kevin J. McGowan, Ph.D, Extension associate at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and co-editor of the second New York State Breeding Bird Atlas, President and webmaster for the New York State Ornithological Association, and a member of the New York State Avian Records Committee (NYSARC). McGowan is an authority on the crow family, and has done extensive research in social development, family structure, and West Nile virus transmission within avian populations, especially the American Crow (Corvus brachyrhynchos). He is a Senior Course Developer and Instructor at the Bird Academy, you can find out more about his classes here.